Cataloging

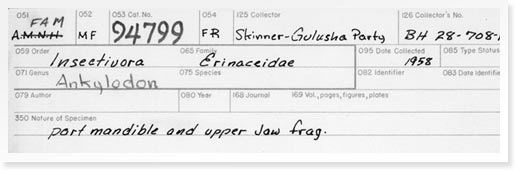

Cataloging is the process by which all the parts of a specimen are linked to the information associated with them through a unique identifying number – the catalog number. A specimen is cataloged by the physical process of entering its associated data in the relevant database, archival card catalog, or ledger.

Even if the specimen itself is later lost or destroyed, the catalog entry remains as a permanent record of the original specimen. The importance of creating this record, by the physical process of data entry and labeling, cannot be understated. For natural history collections, a large fraction of the scientific value of the specimen is tied to its associated data. The catalog number is the link between the specimen and the data; if this link is broken, then the specimen may lose much of its usefulness for research and education.

Some people use the words “cataloging” and “accessioning” interchangeably, but, as we discussed in the section on accessioning, the act of cataloging and accessioning may or may not be the same thing. An accession record contains issues that are most relevant to ownership of the specimen; for example, how and when it was acquired, whereas catalog records allow you to assess what you have, what condition it is in, and where it is. The catalog is the intellectual link to your collection and the key to the physical specimens. The bigger a collection is, the more important this organizational link becomes.

Catalog numbers are of vital importance when specimens are used for research. Specimens are always referred to by their catalog number in scientific publications. This enables other researchers to reference the specimen in their publications, or to confirm or reject the observations of other scientists by directly examining the specimen themselves. Citing the catalog number makes sure that everyone is looking at the same specimen and the same set of associated information.

What is a catalog number?

A catalog number is the unique identification number for a particular item or group of items. You mark the catalog number on the object, and create a catalog record for each number. The number links the object and the documentation. This number may be different from an accession number that identifies the transaction that establishes ownership of the object or group of objects.

Chapter 3: Cataloging of the National Park Service’s Museum Handbook, Part II: Museum Records is available online here.

It may not be possible to catalog newly excavated fossils until enough preparation work has been done to identify the specimen. It is important that the person who does the cataloging knows enough about the specimen, its origin, and the collection generally to make accurate identifications, detailed observations, provide cross-references to related objects, and place the specimen within the context of the larger collection. Whether you are cataloging onto a paper worksheet, a catalog card, a ledger, or a computer database, you should always follow the same format to ensure consistency. In a computerized database each piece of information is entered into a separate field, which is the specified area used for this particular type of data (see Databasing).

The simplest cataloging system involves applying numbers in a numerical sequence, starting with number 1 as the first specimen cataloged. More complex systems may be able to impart some useful information simply by viewing the number. For example, the catalog number can consist of the year, an excavation identifier and crate number e.g. 2008-12A-2512.

Tips on how to catalog

- A useful general guideline is to assign one unique number to one specimen for which the information is unique. Specimens of different species, localities, stratigraphic units, collection dates, collectors, publications, etc., should not be mixed. Don’t group specimens together under the same number, or assign different numbers to different parts of the same individual. There will occasionally be exceptions to this rule – e.g., large collections of fragments from the same species and locality, or expedition situations in which the collectors cannot be sure whether the parts found in the field belong to the same individual. In such cases a judgment will be necessary to catalog these as individual specimens or a specimen lot.

- For specimens collected as part of an excavated series, numbers should be assigned in the same sequence as excavation numbers if possible. Adding the new specimen catalog numbers to the collector’s excavation catalog, can help ensure adequate cross-referencing, although it is essential to make a clear distinction between the original records and any additional information added later. It is always a good idea to establish a system for “signature annotations” so that later workers can tell who altered or annotated an earlier record.

- Where information on a specimen is missing or absent, the catalog field should be left blank.

- It is important to ensure that cataloging is completed as thoroughly and comprehensively as possible. Future users will work from the assumption that the catalog card represents the best data available on the provenance of a specimen.

- If two specimens are embedded in the same block of matrix, but need to be differentiated, each should be given a different number.

- If a mold or cast (latex, plaster, etc.) has been made from a specimen, it can be assigned the same number and differentiated by a suffix, or better, an extension number.

What are the most common mistakes and problems when cataloging?

- Applying the same number to two or more specimens. This can occur for a number of reasons, of which the most common is labeling the specimen, but delaying or forgetting to enter the data into a card, ledger, or database. When the catalog is examined, it looks like the number is still available for allocation, and then can be “doubly-assigned”. Another source of error is when numbers are re-used. For example, a specimen is assumed to be lost, so it is deaccessioned and the original number reassigned to another specimen. At a later date, the first specimen is rediscovered; there are now two specimens with the same number. For this reason, it is good practice to assign a number once, and once only; numbers assigned to lost or deaccessioned specimens should be retired, not re-used, and the catalog updated to reflect this information.

- Giving two numbers to the same specimen. The commonest cause of this error is when a specimen is not labeled promptly after cataloging, or if not all parts of a specimen are cataloged. At a later date, the unlabelled specimen part is discovered in the collection and is assumed to be uncataloged.

- Transcription errors. For example, making a mistake when writing the number. These can occur during the creation of catalog records, or during labeling of specimens. The end result is usually two specimens with the same number, which also breaks the link between the original specimen and its data. For this reason, it is important to work carefully and methodically when cataloging, checking back to the original catalog record frequently while labeling specimens.

- Identification errors. Sometimes, the parts of more than organism can be mixed up in the site. If care is not taken in checking and identifying the specimens prior to cataloging, multiple specimens may be cataloged under the same number, or a single specimen may end up with more than one catalog number. It is somewhat easier to resolve the first problem (where a new number can be assigned to the second specimen) than the second (which necessitates the retirement of one or more numbers).

Links

- For more on cataloging download the following procedures from the American Museum of Natural History’s Department of Paleontology:

- Chapter 3: Cataloging of the National Park Service’s Museum Handbook, Part II: Museum Records is available online here.